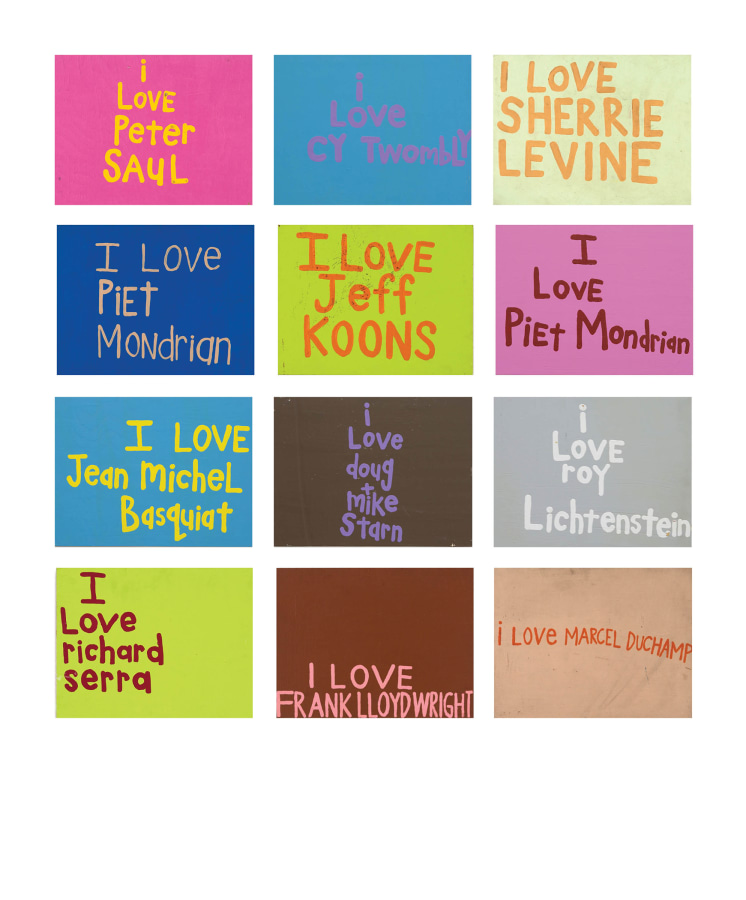

Cary Leibowitz, I Love…., 1990. Latex paint on wood panel, 12 panels, 12 x 16 in. each. Courtesy of the artist and INVISIBLE-EXPORTS.

Fantasy love is much better than reality love. . . . The most exciting attractions are between two opposites that never meet.1

Cary Leibowitz loves Andy Warhol, as he has stated in his paintings and interviews. The repeated sentiment, meant to express fandom and admiration rather than suggest a personal relationship, makes one think of a teenage obsession with a favorite celebrity. Leibowitz, whose work plays with notions of naiveté and self-deprecating humor, may feel a connection with the late 1960s Pop Art icon, who was notorious for being eccentric, ambiguous, openly gay before it was a social norm, and prone to deflecting attention from himself onto those around him. Leibowitz and Warhol share an obsession with celebrity, which reveals itself in their artworks that simultaneously examine popular culture and art history. For example, Warhol made numerous brightly colored, graphic screen print portraits of movie stars (e.g. Marilyn Monroe), musicians (e.g. Mick Jagger), art collectors (e.g. Marcia Weissman), pop culture figures (e.g. Jackie Onassis Kennedy), politicians (e.g. Mao Zedong), monarchs (e.g. Queen Elizabeth II), athletes (e.g. Muhammad Ali), and even several self-portraits.

Warhol made these works in his New York studio, The Factory. The name Factory implies that the artwork was produced under similar circumstances as industrial goods, where long lines of workers make replicas of a product. This form of production skewed the notion of art as a unique creation made by the artist’s hand and highlighted the newly emerging commercial art market of the mid-century. Likewise, Leibowitz makes multiples in the form of cheap items such as yo-yos, scarfs, and hats with campy to dark comments, such as “Fran Drescher Fan Club” beanies and “Misery Rules” flags. Unlike Warhol’s multiples that were never inexpensive, Leibowitz’s tawdry multiples further Warhol’s original challenge on art production by rejecting the exclusivity of the art market.

Cary Leibowitz, I Love…., 1990. Latex paint on wood panel, 12 panels, 12 x 16 in. each. Courtesy of the artist and INVISIBLE-EXPORTS.

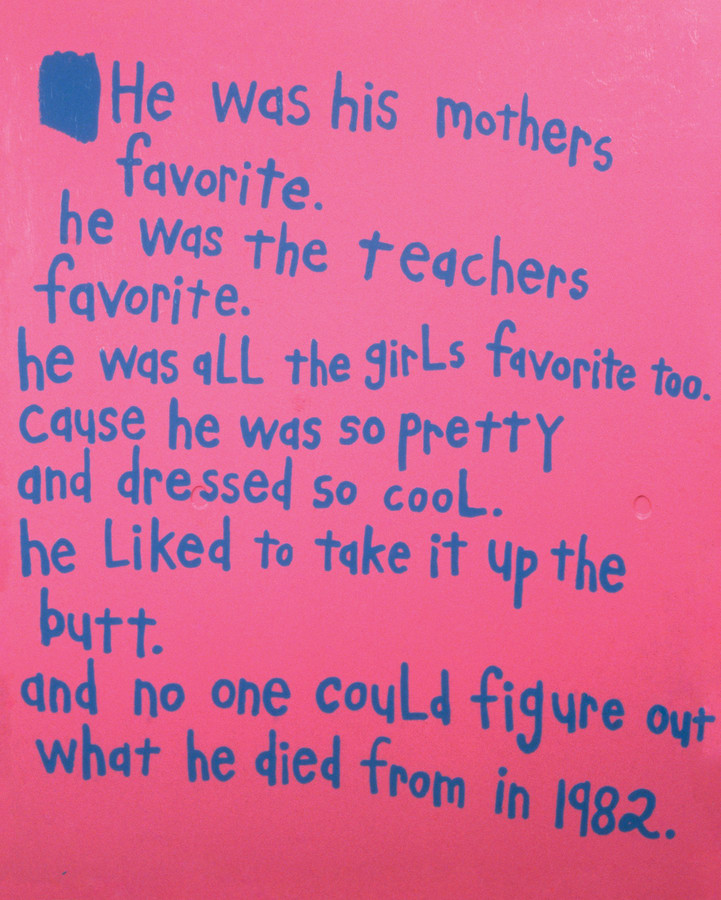

Leibowitz expresses his obsession with his own celebrities in the painting series I Love… (1990), in which bright colored letters spell out exclamations of love for famous artists, sometimes more than once: "I Love Peter Saul," "I Love Cy Twombly," "I Love Sherrie Levine," "I Love Piet Mondrian," "I Love Jeff Koons," "I Love Jean Michel Basquiat," and so on. The exuberance of his fandom is felt in the simplistic and yet heartfelt phrase, perpetually linking Leibowitz to his idols. In the painting I Love Warhol Piss Paintings (2007), Leibowitz proclaims his admiration for a series of Warhol’s paintings where the artist used urine as a medium to stain canvases or oxidize metal plates or canvases prepared with metallic grounds. Like much of Warhol’s art, this evocative series challenged the status quo of art making during the 1960s and 70s. The splattered and dripped urine references the great modernist styles of Jackson Pollock and Helen Frankenthaler, and yet the use of human waste and dirt from the street makes Warhol’s paintings less precious and pokes fun at the dogma of American Modernism. One might even say that Warhol’s Piss Paintings are precursors to the crude aesthetic of Abject Art in the 1990s, when Leibowitz first made his appearance. Bulgarian-French philosopher Julia Kristeva first discussed the concept of abjection in her 1980 book Powers of Horror where she defined abjection as “the state of being cast-off.” In relation to painting and sculpture, abject art uses particular subject matters or materials to cause a sense of repulsion often associated with uncleanliness or bodily functions. While many abject artists, such as Paul McCarthy and Cindy Sherman, use the body and its functions figuratively, Leibowitz sources the abjection in his art through the use of words and the oddity of their display. For example, a periwinkle blue and hot pink painting, titled He Was his Mother’s Favorite (1987), reads:

He was his mothers

favorite.

he was the teachers

favorite.

he was all the girls favorite too.

cause he was so pretty

and dressed so cool.

he liked to take it up the

butt.

and no one could figure out

what he died from in 1982.

This uncanny narrative implies a deeper philosophical and human response, empathy for the protagonist and repulsion for society’s nonchalance over the critical issue of the AIDS epidemic. More than any other topic, Leibowitz turns to himself as the subject of scrutiny: “Do these pants make me look Jewish?”; “Ugh he’s crying again.” Simple questions and comments that take root in the belly of most people’s insecurities.

Cary Leibowitz, He Was His Mother’s Favorite, 1987. Latex paint on wood panel, 60.25 x 48 in. Courtesy of the artist and INVISIBLE EXPORTS.

Despite having such an appreciation for others, Leibowitz and Warhol are known for their loner and loser mentalities. While it may be part of an aesthetic, it also correlates to a personal philosophy adopted by both Leibowitz and Warhol. In 1975, Warhol wrote a book of philosophy on the topics of Love (Puberty), Love (Prime), Love (Senility), Beauty, Fame, Work, Time, Death, Economics, Atmosphere, Success, Art, Titles, The Tingle, and Underwear Power, titled The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). Each chapter reads in a conversational tone with passages ranging from long narratives to one-line musings about life—all from the perspective of Warhol. One of the artist’s philosophies responded to the issues of being alone. He wrote:

[P]eople who imagine me as the 60s media partygoer who traditionally arrived at parties with a minimum six-person ‘retinue’ may wonder how I dare call myself a ‘loner,’ so let me explain how I really mean that and why it’s true. At the times in my life when I was feeling the most gregarious and looking for bosom friendships, I couldn’t find any takers, so that exactly when I was alone was when I felt the most like not being alone. The moment I decided I’d rather be alone and not have anyone telling me their problems, everybody I’d never seen before in my life started running after me to tell me things […]. As soon as I became a loner in my own mind, that’s when I got what you might call a ‘following.' 2

Although he did not want to be alone, by adopting the persona of a loner he drew people in, or at least he believed this to be true (despite the fact that he was one of the most famous and profitable American artists). This seems to be a bit of reverse psychology—I don’t want you, therefore you want me, and vice versa. Warhol was very shy, so this tactic worked well for him. Because of his bashful proclivity to making friends, he watched a lot of television that allowed him to have imaginary friendships with those on the screen. In his desire to be liked, he wanted to have his own TV show called Nothing Special, an ironic title that plays to his blasé self-opinion.3 In a similar way, Leibowitz creates an image of the everyman, the no man, with his self-effacing style. One can read each of Leibowitz’s text paintings as an outpouring of personal philosophy that shapes the artist’s persona with humor, empathy, camp, and Americana.

Leibowitz and Warhol perfected the art of self-deprecation and deflection to create a counter effect of magnetism. One has a hard time resisting the work of these two artists as it entertains our popular culture desires, while simultaneously presenting ideas rich with criticism of art and life. Holland Cotter wrote, “Cary Leibowitz, you might say, is a child of Andy Warhol […]. He turns a persona of self-abasing narcissism into art.”4 And from this lineage, art has transformed into a philosophy for human connection.

1 Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) (New York: Harcourt Publishing, 1975), p. 44.

2 Ibid, p. 23.

3 Ibid, p. 147.

4 Holland Cotter, “ART IN REVIEW; Cary Leibowitz—‘Gain! Wait! Now!’” in The New York Times, December 14 2001.

Lauren R. O’Connell is a curator and writer focusing on modern and contemporary art. Formerly, she worked at the UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA) where she focused on the support and development of new exhibitions, including Andy Warhol: Still Lifes and Portraits. Prior to BAMPFA, O’Connell worked at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. She received an MA in curatorial practice from the California College of the Arts in San Francisco and a BA in classics and art history from the University of Arizona.

For more 36 Windows blog entries, click below.

Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show is organized by The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

Lead sponsorship is provided by Gaia Fund. Major sponsorship is provided by Dorothy R. Saxe and Wendy and Richard Yanowitch. Supporting sponsorship is provided by Pacific Heights Plastic Surgery. Additional support is provided by David Agger; Alvin Baum and Robert Holgate; and Michael T. Case and Mark G. Reisbaum.

The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibition program is supported by a grant from The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Installation view of Cary Leibowitz: Museum Show, on view Jan 26, 2017–Jun 25, 2017 at The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco. Photo by JKA Photography.