Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Untitled [Portrait holding mask], 1947. Gelatin silver print. © Jersey Heritage

This piece was originally published in the Show Me as I Want to Be Seen exhibition catalog.

—Claude Cahun

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Untitled [Portrait holding mask], 1947. Gelatin silver print. © Jersey Heritage

Our time is up. I know this by the empty houses. We had fifty years of fortune-telling and unclean work. In a distant marble palace someone penned a paper that said we are bad again. The mines are scraped, the forest is quiet, it’s the second drought in a row, and they need someone to suffer for it.

I should have left with the others.

The tree this staff was carved from is dead. Each step threatens to snap it against the hard soil. The herbs in my vials have lost their potency, I have traded the amulets of my god for enough food and water to cross the next horizon. My neck is naked and faithless.

The staff breaks, jolting me from my sleeping walk. My arm is so numb, the staff feels like leaving part of myself behind.

I’m very tired. Has anyone been tired before? In history? Possibly.

Hell is not a special place. It is an extension of our life on earth. In hell we fall forever. The idea of heaven is that you finally stop falling.

At the edge of town I smoke the rest of my pagan leaf, coughing as I uncork my vials and dump rue, laser, pennyroyal into the creek. Fish nibble and dart away.

Photo: Johnna Arnold

I can eat at the inn if they don’t think I’m a Zannoi. I remove the piercing from my tongue, shed my coat with its quaint ancestral patterns. But some things I can’t remove.

On my back there is ink under the skin, punctured like a snake’s bite when I was twelve, old enough for a bit of culture to enter my body. A stain on my tailbone, where the breath of life entered my spine.

I bathe alone.

I don’t even remember what the symbol looks like. I think I once held a polished bronze circle behind me, tried to see it in the blur, but I never had much curiosity about it. It was just a thing that happened, like a childhood fever.

Hot weather. The sun is suspicious of me, wants me to loosen my sleeves, strip down to my undershirt. Why is she sitting there sweating in such heavy clothes?

I lay in the cedar-smelling room of the inn and have pretend conversations about what I would say if someone accused me. I imagine myself groveling, ingratiating myself, distancing myself from my own kind, and finally, begrudgingly, we come to an agreement. How sweet the understanding.

I get a job so I can afford the caravan north, where family are strewn.

Heat reflects from the mountain with its throbbing veins of glass. Hauling rocks for the new road.

Stupid me. Everyone is taking their shirt off. Flat, sweaty breasts, we’re lean out here, even we and they share that. The milk is the same. If I were ever to raise a child, I would keep their skin clean, their words neutral, balanced between the square of the mountains, the marsh, the forest, the flat lands. I’d want them to be able to go anywhere.

I take my shirt off and I’m the only one here with sweat like ice. I keep my back to the mountain, shoulder blades twisting like knees under a blanket. I splash myself with the bucket they’re passing around, then throw my shirt back on.

Isabel Yellin, Erin/Heather, 2017. Leatherette, acrylic, and stuffing. Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery.

A woman corners me on the way home. She knows, somehow, and I’m ready to run, but she just says: can you do for my child? I can do. She’s country, hinterland mothers like her have been coming to us for a long time, it’ll take a bit before the city hate spreads to her, before she sees and understands, through certain events transpiring in the public square, or perhaps by a deep enough body of water, how serious the matter is.

As I walk the road to her house I wonder if someone paid her to lure me out here.

I go through the trees in the back, beetles crawling in the bark. I look through the oily window. Just her and her child.

I haven’t been near a child for a long time. I cross the street when I see one. They say we steal children. And everything else that can be done to a child.

I crush petals and smear them across Sand’s forehead, I tried not to learn her name, but it was crammed past my ears. Her skin burns my fingers. I try to look calm, but she doesn’t have the look of life about her. Some spirits give up faster than others.

If the heat breaks her heart they’ll come for me.

I tell the mother I need an animal. There are snakes around here, but it has to be a good animal, one that is cared about. Why else should the gods care?

She has a tars. Domesticated, large for its breed. I was hoping to keep the mess on a plate.

She looks away as I run my hand along the collar, remove the wooden lozenge that bears its name. I want to ignore it but I force myself to read it. Two names now. Every step of this has to involve care. The rest of the world is for looking away, but here, we look, and let ourselves hurt— it has to hurt.

The name is Anyit. It—she—has big wet eyes. I run my hands across her fur. Feathery, stubby antennae like bulrushes wiggle at my chin.

The mother seems angry. It is at this moment they are most likely to question, most likely to turn on me.

I concentrate on the tars’s eyes. She trusts me. I take strength from this. I give her pain, then darkness.

Things become easier after something irrevocable has happened. They are invested now.

The mother gives me coins and for a little while this evening she will feel hope. She will hold her daughter’s hand and feel the peace she felt before. For a time.

I walk faster through the brush.

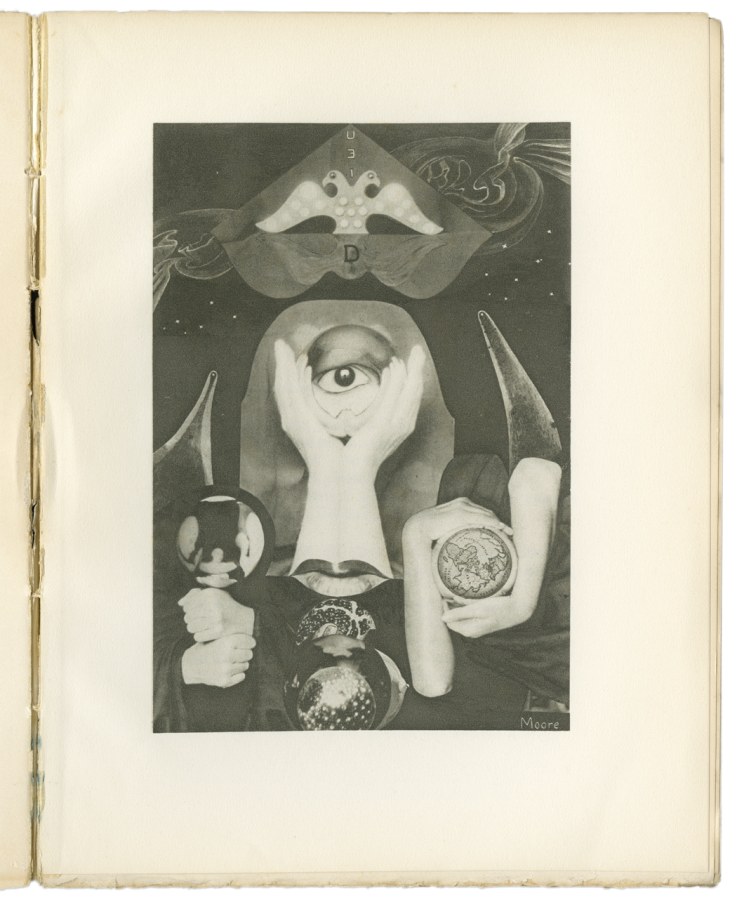

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Frontispiece to Aveux non avenus. Paris : Éditions du Carrefour, 1930. Reproduction of photomontage, approx. 8 7/16 x 6 1/2 in. Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Library.

Each province is divided by an oath-line. If a Zannoi passes the line without the proper writ, the food in their stomach will turn to gravel and their blood will write the capstone verses on the nearest surface—or that is the oath we swear. It is a disgusting, wet, lengthy oath. In summer we swear it in the sun, in winter we swear it in the river.

I rent a room in a quiet boarding house and peer through the blinds at people laughing in the street below, admiring them like dolls.

Remove my skin and start again. I wish I’d dreamed it innocently. But no, I wish it, how detestable. It is no vision, only my sorry little wish.

Our beliefs are not so different from the majority faith. We worship the same god. Most Zannoi don’t even perform divinations or sell dubious potions, what I am is just a splinter of a splinter. So why do we persist in our difference? It would be so simple! Shave the bones of my face a little flatter, suck the ink from my back, tweak the strings running from my brain to my tongue so I can pronounce certain words properly. We could disappear into them in generations.

Some of us do, and then we are lost to history, taken from the hot pan, when you are in the pan it feels like the most important place in the world. Why am I so afraid to stop hurting? Why do we cling to the heat at the center of the earth instead of letting ourselves be shaken off into the cold void?

Why don’t I recant my body?

We are the idea that there are things worth dying for.

God created me. I know this because my soul hurts inside me. I deserve it. There is a lot of bad in me. I hurt animals, I take women’s money even if I know what I have done won’t help them, I steal when I think no one could possibly ever find out. There’s an inertia to it. I think about getting a terrible burn on my back, my face, my tongue, I’d be deformed but I wouldn’t be a Zannoi. Maybe the deformed think that about us.

I told my aunt how bad I was once, after I’d crushed a kitten and hid it under the porch. Told her I didn’t deserve a thing in the world. She said, sweetie, people like you need love more than anyone.

I just cried. I was very upset, I think that’s why I’d said it. I thought the kitten moved, I ran and banged my face into a porch support. Blood all over me, more than I could staunch with those little fingers.

She tilted my head back and told me to pinch my nose, watched with a strange worry in her eyes. When children played in the quarry she worried over me, held me back unless she knew someone was looking out for me, told me not to run so fast, and tucked a rag into my pocket.

Gabby Rosenberg, You Again?!, 2018. Acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Steve Rimlinger.

I look at their lives, shooting so smoothly through time, and it looks like nothing. I can’t imagine that simplicity

There are disagreements among our kind as to which remedies are appropriate for a practitioner, as to which are not remedies at all but simply barbarous rites that shame us before our host cultures. I carried vials of pregnant horse piss, my aunt taught me to shatter the unborn in the womb, we lost family over it, moved to separate houses, we fracture, and fracture again, whittled away by scriptural interpretations and medicinal schisms, because in the end, we don’t even like each other.

I make a friend at work. She laughed at a joke I didn’t even know I was making. She shares her flask with me, a disgusting drink, made with the tingling fruit we do not consume. But I drink it, a small sin to conceal my god from her. My fingers twitch with the signs for absolution, a motion I hide by playing with my hair.

Her name is Orn. These people have such ugly names. God crafted you with immaculate care and you give a child a name like a rabbit dropping?

She takes me home. I haven’t touched someone of her faith since I was too young to know better. Her wholeness is like bathing in milk.

I dream of my family. I remember nothing but feel everything. I turn over in bed and kiss her to wash the taste clean. We hold the kiss, her saliva trickles inside me, please be etcher’s acid, please be the hot blood of mountains. Am I changed? She embraces me, touching the small of my back in the dark. To her fingers my skin feels like any other.

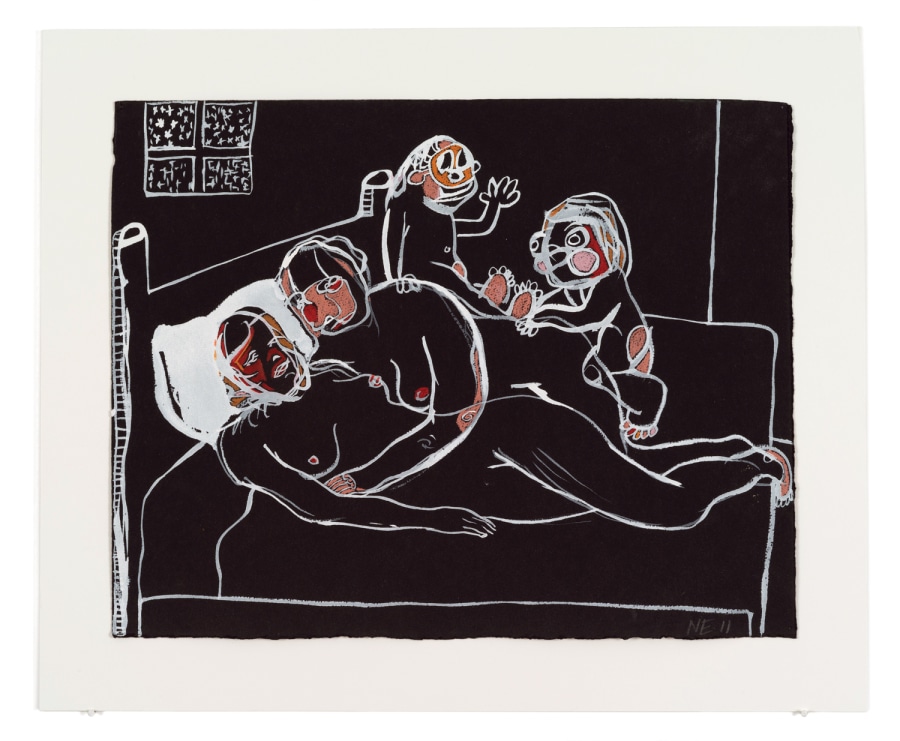

Nicole Eisenman, Untitled 11, 2011. Mixed media on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Photo: John Berens.

Days sprout to weeks, weeks thicken to months, too gnarled to uproot without skinning the hands of my heart.

We walk home together after work.

Happy. Happy. Happy. Happiness is boring, it can’t be recorded, skin without scars, smooth and forgettable. Happiness is amnesia, it is happening to a different person than the one who is miserable. What benefit is it to them?

She gives me a necklace. A silver triangle with a rune inside. It looks familiar but I don’t know it, not in the heat of us.

I put it around my neck.

We grind in the dark, the sigil on my tailbone pressed against the sweaty sheets.

When we fuck, I am part of her ethnic purity. I am no longer greasy and broken, it is pleasure, it is relief. But this night, there is a moment when she’s sunk to the hilt on me, I’m being absorbed, swallowed, a pebble sucked into mud, it’s too much, I don’t have the substance to couple with this engine, but she is part of me, I know that now. I don’t know when they first put her purity in me, but I’ve been carrying her purity on my back, I’m fucking the boulder that is me, it’s crushing me into paste, crushing the bed into the floorboards, red paste oozing through the cracks into the kitchen below, I want to thrust her off, but no part of me belongs to me except the pain of experiencing that I am not myself.

Photo: Johnna Arnold

Another night.

She’s very drunk. I went all my life without tasting that drink of hers, so I have no tolerance for the stink of it. I say, “want to give me a massage?”, and roll over with stupid innocence, thinking myself one of her.

Her hands flow softly onto me, nursing the knots from my shoulders.

Her fingers are stiff as harpy talons, framing my tailbone.

She touches it, the feeling is incredible, it burns hotter than my breasts, my genitals, I never imagined one of them would touch it with naked fingers.

She recoils.

I read her face: You kill babies. You poison spouses. You change boys to girls.

I make it to the porch, shirtless under the moonlight, before she catches me by the necklace. She drags me across the dirt, I kick and claw, I’ve never had so little breath to regard the sky, it seems dull as ceiling, stars like mold speckles. The chain breaks, she picks up the triangle symbol and rubs it furiously against her shirt like a stain that will never come out.

“It’s not for you!”

Little bits of the chain litter my neck like scales.

I bite her leg and she kicks me, she is gone, leaving only the taste of dirty copper welling at my gums.

Photo: Johnna Arnold

Part of me prepared myself for this moment. To be Zannoi is to have things taken away. I experience hurt like holding a stone separate from my body, but it means I hold everything else outside my body. Joy is only sleeping with stones.

I tell myself this.

I walk quickly through the dusk, climb a fence, cross a droughty crack of earth, rustle through dead maize husks, march into a coop and snap a bird’s neck, saying the prayer one says when you snap a bird’s neck.

Every time I think I will make a definite change in my life I kill a small animal. This has set back my personal growth immensely.

An egg, nestled in the straw, still hot from the bird’s body. The warmth of creation, of one thing separating to become two.

It tore me when I split in half. I know this now. I should have been kinder to the wound.

My legs carry me back to the village. I stop myself. They’ll take me in the dark.

Only one thing can wash a Zannoi from your skin. When I was eleven, I read my aunt’s books–there was a particular woodcut. I used to masturbate to how they did it. It was safe inside that final mutilation. I think that must be what heaven feels like.

Morning comes and she’s at work, hair tied back, face severe under the sun. I’m in the trees at the edge of the road, thin as a wall, if a rider passes on the plain behind they’ll see me from miles away.

She drops the rock she was hauling. Walks this way, to the dead grass. We used to piss together.

She’s wearing a cropped top, her belly sun-burnt and ripe. If I had her guts on the ground I could tell you the name of your child, where the bats sniff for gold, what color to paint your lips if you want to fall in love in winter.

But she is not an animal. They are designated for the shedding of blood, they are smaller parts of ourselves, taken in token.

No. I thought I was being strong, killing only animals. But a sacrifice should be what I don’t want to do.

I don’t want to take this rock to her temple. It would hurt me terribly.

She sees me, filthy sweating torso, breasts sticking with bark.

I’m too weak. The rock slides from my hands.

“Please.” Please. Whoever invented this word must never have had to use it.

She screams like the smoke pouring from a furnace.

It can’t get any worse than this, my aunt would say, smile cut across her face by the knife of years.

I thought she knew something but I guess she didn’t.

They’ll be waiting in my room, where I hid the money for the caravan, and more. I should have kept moving.

Claude Cahun (Lucy Schwob) and Marcel Moore (Suzanne Malherbe), Untitled [Portrait lying on leopard skin], 1939. Gelatin silver print. © Jersey Heritage

I find broken glass in the window of an overgrown house. God has given me teeth.

Bumps raise on my skin as I wade through the swamp, I’m too tired to swat the bugs away.

God has not placed into the world anything we cannot endure, this is the promise. I felt god with me as a child, in the animals I broke for her and hid under the porch. The purity of the feeling convinced me it was from god. Would the shadow of god be permitted to deceive a child? I could enumerate the tiny bones in their necks, the creamy furs I felt under my fingers. Would that help to decide?

I take the glass shard from my pocket and look to the water for a reflection, twist til my spine aches. I see the blemish on my tailbone, in the dim ripple it could be a smear of dirt. I touch the jagged edge to the ink, is that the ink? It all hurts the same under the knife. Such a cunning brand, the most deceptive odorless poison. Your skin whispering secrets to the world.

I see the circle outlining the symbol, the symbol unreadable like a dream. The reflection is muddied with mosquito eggs like black rice. I cut between the smallest specks of life to find my deformity.

Just a small cut. The circle is not so large.

Davina Semo, A GREAT THING IN HER LIFE IS THAT SHE HAS A SECRET, 2018. Pigmented and reinforced concrete, stainless steel pipe, and broken auto glass. Courtesy of the artist and Jessica Silverman Gallery, San Francisco.

The blood won’t stop, fast, clotless, I can’t see if the symbol is gone, but I can’t bear to cut anymore.

The caravan north is a broken idea. I’m not just a traitor, I’m a traitor to traitors, they’ll know it by the jagged shadow I’ve made of what is sacred.

What if I’d asked Orn to cut it from me? Maybe she would have admired that. If I had come to her with genuine repentance in my heart, instead of deceiving her into sleeping with an unclean.

I found a red ribbon in my tailbone, it runs through my entire life.

The sun is mounted in the killing position, and the grass below my feet agrees. The little water that falls here has converted itself to brittle blades. The water should never have come, what good is a little yellow grass in a lonely place?

I’m at the oath-line, where the brown has been scraped away to show pale clay hardened by lime. I slide along it, listening for hounds, trying to find the furthest point without crossing. I look for stones large enough to conceal me, I squeeze behind them like props on a stage.

My hand is stuck to my back, but the wet still kisses my palm. Not enough blood for even half of me.

Nature gave me this earth to rest my back on, gave me this boulder to shield me against the sun, and for its mute tenderness I have abused it. I’m sorry, little animals, for twisting your necks, for running a knife across your throats, for plunging you into water. I feel my neck wringing, I feel the water in my lungs, I’m twisting myself to pieces, no, if I stop killing small animals, it will be like how they stop killing us: stop so they can start again, let us earn money so it can be confiscated, let us own land so it can be taken, let us lay fallow. We’re just like those small animals, we have to hurt so real people know they’re real.

My throat cracks for water. I chew my wrist, trying to keep the fever at bay that says bite a little deeper and drink. The oath-line cuts past the boulder, a hair from my cheek. A single rotation of my torso would end this.

A lizard crawls under the rock and falls asleep by my fingertips, warm with life.

Poprentine Charity Heartscape is a writer, new media artist, game designer, and dead swamp milf in Oakland. She makes cursed artifacts and records the endless war. She is a 2016 Creative Capital Emerging Fields and 2016 Sundance Institute’s New Frontier Story Lab fellow, a 2017 recipient of Rhizome’s Prix Net Art Award, and a 2016 Tiptree fellow. Heartscape has exhibited at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, New York, the New Museum, New York, the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. She is the author of With Those We Love Alive, Howling Dogs, Psycho Nymph Exile, and Almanac of Girlswampwar Territory, and has been commissioned by Vice and Rhizome.

The official catalog for Show Me as I Want to Be Seen published is by The Contemporary Jewish Museum with original contributions by Natasha Matteson, Rabbi Benay Lappe, and a newly-commissioned piece of fiction by Porpentine Charity Heartscape.